The word wig is short for Periwig and first appeared in the English language around 1675.

Wigs have been worn throughout history and not just as a fashion item. Looking through history we can see that wigs were worn to demonstrate wealth and importance as well as having a more practical purpose as protection against cold and rain. Wigs were even worn in wars to impress the enemy!

The ancient Egyptians, wore them to shield their hairless heads from the sun and for ceremonial occasions.

In the 16th century a wig would have been worn as a means of compensating for hair loss or improving one's personal appearance. They also served a practical purpose: the unhygienic conditions of the time meant that hair attracted head lice, a problem that could be much reduced if natural hair were shaved and replaced with a more easily de-loused artificial hairpiece. Shaving the head also allowed the wig to sit properly upon the head.

The price of wigs depended on the style and type of hair used in their manufacture. Human hair, horsehair, calve's tails, silk linen, cotton thread and goathair were the most commonly used materials for wig making. To sell one's hair was a useful source of income for poor women and children. Human hair taken from the living was preferred over that taken from the dead, which made it a more expensive option. It was feared that taking hair from a corpse would carry infection onto the wig wearer.

Queen Elizabeth I of England famously wore a red wig, tightly and elaborately curled in a "Roman" style and King Louis XIII of France pioneered wig-wearing among men from the 1620s onwards.

Periwigs for men were introduced into the English-speaking world when Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660. The wigs worn at this time were shoulder-length or longer, imitating the long hair that had become fashionable among men since the 1620s. Their use soon became popular in the English court.

With wigs becoming virtually obligatory garb for men of virtually any significant social rank, wigmakers gained considerable prestige. A wigmakers' guild was established in France in 1665, a development soon copied elsewhere in Europe. Their job was a skilled one as 17th century wigs were extraordinarily elaborate, covering the back and shoulders and flowing down the chest; they were extremely heavy and often uncomfortable to wear. Such wigs were expensive to produce. The best examples were made from natural human hair. The hair of horses and goats was often used as a cheaper alternative.

Usually a wig was greased with scented pomatum, teased or curled with a hot iron and rolled in papers. Other wigs could be rolled with small heated rollers made up of pipe clay, which were called "buckles". Once positioned on the wearer's head, the wig received additional pomatum and an application of powder blown from a small tube.

The wigs of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette's time were immense horsehair erections often with bobbing curls on wires, over which no less than pounds of flour were dusted after the oiling process. Then laces and ribbons and flowers and butterflies of spun glass and fruit and even miniature ships were used as decoration.

The largest wigs ever worn by English women were those of the reign of Queen Anne. A house now in Kensington with a powder room off the back drawing room is said to have been occupied by one of her maids of honor. Besides the Full Bottom wigs, there was a notable list in vogue in England including Bagg wigs, Grecian Flyes, Curly Roys, Airey Levants, Full Bobs, Minister's Bobs, Naturals, and Half Naturals.

In the 18th century, wigs were powdered in order to give them their distinctive white color. Wig powder was made from ground flour, pounce, white earth, starch, plaster of paris, kaolin, or talc, giving the hairpieces a white or off-white greyish color. Wig powder was occasionally colored in pastel tones of violet, blue, pink or yellow. Pounce was originally a powder made from ground cuttlefish bone used as a wig powder in the eighteenth century. The early Parliamentarians in England used potato flour as wig powder. Wig powder was scented with orange flower, lavender, or orris root.

By the 1780s, young men were setting a fashion trend by lightly powdering their natural hair. The British army in George II's reign used 65,000 tons of flour for powdering wigs every year.

After 1790, both wigs and powder were reserved for older more conservative men, and were in use by ladies being presented at court. To raise money for the Napoleonic wars, in 1795, the English government levied a tax of hair powder of one guinea per year. This tax effectively caused the demise of both the fashion for wigs and powder by 1800. Under the French egalitarian regime there was a tax on wig powder in The Hague from 1806. Wigs continued to be worn after 1800 by those in the professions such as doctors, the judiciary, soldiers and clergymen as late as 1829, some were still clinging both to wigs and wig powder.

As wig powder contained starch, rain could make wigs very heavy and uncomfortable. Swift's poem "A City Shower" comically describes how at the sight of rain gentlemen would run for cover 'to save their wigs'.

At the beginning of the 20th Century more freely arranged hairpieces were being used. In the 1920’s short hair cuts became fashionable and the trend for wigs almost disappeared overnight until the 1960’s when the hairpiece as a fashion item became a must and were not being sold in just specialized shops but also in department stores. The strong demand for wigs led to mass manufacture and the development and production of synthetic hair.

Now in the 21st Century there is still a need for wigs and hairpieces for reasons such as; hair loss due to a medical reason; fashion, with a growing trend for hair extensions; parties, and religious requirements.

A small ivory hand on the end of a long slender stick, this was used to relieve the irritation caused by the numerous fleas infesting the elaborate wigs worn by fashionable 18th century women. The wigs were built up over wire foundations and padded out with false hair to reach fantastic heights, vermin were attracted by the powder and pomatum used and caused tremendous itching reachable only by the wig scratcher.

Wigs were worn by both men and women in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, and were as much a part of a fashionable male's dress as his breeches. Wigs became progressively smaller throughout the century, but they retained nevertheless the awkward feature of being, for all practical purposes, fied to the wearer's head unless he happened to find himself alone, no gentlemen could be seen wigless.

The wig scratcher was therefore a boon to every man and woman who wore a wig. The short, straight little fingers of the little ivory hand could be pushed up by the ebony or ivory handle up between wig and temple. Wig scratchers were invariably made with straight fingers, to get in between the wig and the head, can be distinguished by the similar designed back scratcher.

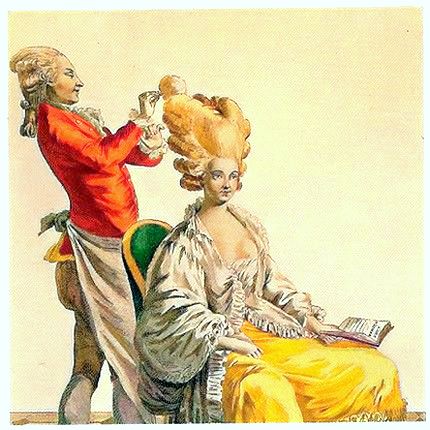

The maintenance of a gentleman's or lady's wig in the eighteenth century was a complicated and time consuming process. The curls had to be kept tight and neat by using a crimper and pomades. Many men and women drenched their wigs in perfume, then powdered it, either by themselves, servant or a professional dresser.

Once the wig wearer was seated and body covered with a sheet, he or she would hold the paper cone over the face to prevent breathing in the wig powder and keep from suffocating while the wig powder was applied.

The powder was applied with powdering bellows or with a flexible tube, called a powdering carrot, it was tube shaped but not unlike that of a carrot.

The powder was poured into the hollow wooden "carrot", and the dresser would blow into the mouthpiece at the broad end, the powder would emerge in a fine cloud from the point. Some powdering carrots were fitted with tiny bellows to produce a stream of air. The carrot was designed up of wooden rings, jointed so that the whole affair is flexible.

In order to allow the nozzle to bend, the three smallest wooden rings were mounted on to leather. Originally there was probably a bulb of soft leather attached to the top of the cone which would have been squeezed to blow the powder out of the nozzle.

This enabled the top of the wig to be powdered without the dresser having to stand on a chair.

How the Wig Was Powdered:

A preliminary operation was to saturate the hair with bear's grease or lard and perfumed oils to assure the adhesion of the powder.

Wealthy people had a special room or closet just for powdering and storing wigs on wig blocks. Louis XIV had his own wig room at Versailles. The "powder room" was just that, a room for powdering wigs, I assume it would have had non carpeted, likely tiled, or wooden flooring as to be easier to sweep up the mess after a wig was powdered. The powder room sometimes had a water closet, suggesting a possible origin of the modern term.

The rooms often only had a set of curtains in the entry instead of a door. The servant in his powdering gown of cotton or linen stood inside the room and the man or woman to be powdered stood back of the curtains thrust his or her head through and then held the curtains clasped about the neck to protect the clothes from the shower of powder which ensued.

Wigs have been worn throughout history and not just as a fashion item. Looking through history we can see that wigs were worn to demonstrate wealth and importance as well as having a more practical purpose as protection against cold and rain. Wigs were even worn in wars to impress the enemy!

The ancient Egyptians, wore them to shield their hairless heads from the sun and for ceremonial occasions.

In the 16th century a wig would have been worn as a means of compensating for hair loss or improving one's personal appearance. They also served a practical purpose: the unhygienic conditions of the time meant that hair attracted head lice, a problem that could be much reduced if natural hair were shaved and replaced with a more easily de-loused artificial hairpiece. Shaving the head also allowed the wig to sit properly upon the head.

The price of wigs depended on the style and type of hair used in their manufacture. Human hair, horsehair, calve's tails, silk linen, cotton thread and goathair were the most commonly used materials for wig making. To sell one's hair was a useful source of income for poor women and children. Human hair taken from the living was preferred over that taken from the dead, which made it a more expensive option. It was feared that taking hair from a corpse would carry infection onto the wig wearer.

Queen Elizabeth I of England famously wore a red wig, tightly and elaborately curled in a "Roman" style and King Louis XIII of France pioneered wig-wearing among men from the 1620s onwards.

Periwigs for men were introduced into the English-speaking world when Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660. The wigs worn at this time were shoulder-length or longer, imitating the long hair that had become fashionable among men since the 1620s. Their use soon became popular in the English court.

With wigs becoming virtually obligatory garb for men of virtually any significant social rank, wigmakers gained considerable prestige. A wigmakers' guild was established in France in 1665, a development soon copied elsewhere in Europe. Their job was a skilled one as 17th century wigs were extraordinarily elaborate, covering the back and shoulders and flowing down the chest; they were extremely heavy and often uncomfortable to wear. Such wigs were expensive to produce. The best examples were made from natural human hair. The hair of horses and goats was often used as a cheaper alternative.

Usually a wig was greased with scented pomatum, teased or curled with a hot iron and rolled in papers. Other wigs could be rolled with small heated rollers made up of pipe clay, which were called "buckles". Once positioned on the wearer's head, the wig received additional pomatum and an application of powder blown from a small tube.

The wigs of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette's time were immense horsehair erections often with bobbing curls on wires, over which no less than pounds of flour were dusted after the oiling process. Then laces and ribbons and flowers and butterflies of spun glass and fruit and even miniature ships were used as decoration.

The largest wigs ever worn by English women were those of the reign of Queen Anne. A house now in Kensington with a powder room off the back drawing room is said to have been occupied by one of her maids of honor. Besides the Full Bottom wigs, there was a notable list in vogue in England including Bagg wigs, Grecian Flyes, Curly Roys, Airey Levants, Full Bobs, Minister's Bobs, Naturals, and Half Naturals.

Wig Powders:

In the 18th century, wigs were powdered in order to give them their distinctive white color. Wig powder was made from ground flour, pounce, white earth, starch, plaster of paris, kaolin, or talc, giving the hairpieces a white or off-white greyish color. Wig powder was occasionally colored in pastel tones of violet, blue, pink or yellow. Pounce was originally a powder made from ground cuttlefish bone used as a wig powder in the eighteenth century. The early Parliamentarians in England used potato flour as wig powder. Wig powder was scented with orange flower, lavender, or orris root.

After 1790, both wigs and powder were reserved for older more conservative men, and were in use by ladies being presented at court. To raise money for the Napoleonic wars, in 1795, the English government levied a tax of hair powder of one guinea per year. This tax effectively caused the demise of both the fashion for wigs and powder by 1800. Under the French egalitarian regime there was a tax on wig powder in The Hague from 1806. Wigs continued to be worn after 1800 by those in the professions such as doctors, the judiciary, soldiers and clergymen as late as 1829, some were still clinging both to wigs and wig powder.

As wig powder contained starch, rain could make wigs very heavy and uncomfortable. Swift's poem "A City Shower" comically describes how at the sight of rain gentlemen would run for cover 'to save their wigs'.

At the beginning of the 20th Century more freely arranged hairpieces were being used. In the 1920’s short hair cuts became fashionable and the trend for wigs almost disappeared overnight until the 1960’s when the hairpiece as a fashion item became a must and were not being sold in just specialized shops but also in department stores. The strong demand for wigs led to mass manufacture and the development and production of synthetic hair.

Now in the 21st Century there is still a need for wigs and hairpieces for reasons such as; hair loss due to a medical reason; fashion, with a growing trend for hair extensions; parties, and religious requirements.

Wig Scratchers:

A small ivory hand on the end of a long slender stick, this was used to relieve the irritation caused by the numerous fleas infesting the elaborate wigs worn by fashionable 18th century women. The wigs were built up over wire foundations and padded out with false hair to reach fantastic heights, vermin were attracted by the powder and pomatum used and caused tremendous itching reachable only by the wig scratcher.

Wigs were worn by both men and women in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, and were as much a part of a fashionable male's dress as his breeches. Wigs became progressively smaller throughout the century, but they retained nevertheless the awkward feature of being, for all practical purposes, fied to the wearer's head unless he happened to find himself alone, no gentlemen could be seen wigless.

The wig scratcher was therefore a boon to every man and woman who wore a wig. The short, straight little fingers of the little ivory hand could be pushed up by the ebony or ivory handle up between wig and temple. Wig scratchers were invariably made with straight fingers, to get in between the wig and the head, can be distinguished by the similar designed back scratcher.

Powdering carrots:

The maintenance of a gentleman's or lady's wig in the eighteenth century was a complicated and time consuming process. The curls had to be kept tight and neat by using a crimper and pomades. Many men and women drenched their wigs in perfume, then powdered it, either by themselves, servant or a professional dresser.

Once the wig wearer was seated and body covered with a sheet, he or she would hold the paper cone over the face to prevent breathing in the wig powder and keep from suffocating while the wig powder was applied.

The powder was poured into the hollow wooden "carrot", and the dresser would blow into the mouthpiece at the broad end, the powder would emerge in a fine cloud from the point. Some powdering carrots were fitted with tiny bellows to produce a stream of air. The carrot was designed up of wooden rings, jointed so that the whole affair is flexible.

In order to allow the nozzle to bend, the three smallest wooden rings were mounted on to leather. Originally there was probably a bulb of soft leather attached to the top of the cone which would have been squeezed to blow the powder out of the nozzle.

This enabled the top of the wig to be powdered without the dresser having to stand on a chair.

How the Wig Was Powdered:

A preliminary operation was to saturate the hair with bear's grease or lard and perfumed oils to assure the adhesion of the powder.

The Powder Room:

Wealthy people had a special room or closet just for powdering and storing wigs on wig blocks. Louis XIV had his own wig room at Versailles. The "powder room" was just that, a room for powdering wigs, I assume it would have had non carpeted, likely tiled, or wooden flooring as to be easier to sweep up the mess after a wig was powdered. The powder room sometimes had a water closet, suggesting a possible origin of the modern term.

The rooms often only had a set of curtains in the entry instead of a door. The servant in his powdering gown of cotton or linen stood inside the room and the man or woman to be powdered stood back of the curtains thrust his or her head through and then held the curtains clasped about the neck to protect the clothes from the shower of powder which ensued.

Alternately, the wig wearer sat in a chair in the powder room and wore a special dressing gown while holding a paper cone over their face to avoid getting covered in the powder.

Other types of furniture may have been found in the powder room, the "poudreuse" and the "coiffeuse". The French word poudreuse means "powder" or "dust". When applied to furniture, it refers to a place originally used as a place to powder hair. A poudreuse was usually made up of a soft brown wood and sometimes had a marble top, which opened to reveal a mirror that could be raised on a rack. The two side leaves fold out to right and left or hinged lids flanking the central mirror compartment coule be lifted to reveal compartments inside. Beneath were compartments or drawers for wigs, comb and brush, pomades, scents, powder, hairpins, patches, and peppermint water.

To sit at the poudreuse, the powder chair known as the "fauteuil à poudrer" in French was used.

As the fashion for face makeup became more popular, the poudreuse evolved into a larger piece known as the coiffeuse. Coiffeuses were often decorated with ornate marquetry inlays. The coiffeuses held the same articles as the poudreuse, if not more. Later the mirror was no longer hidden but rotated between two posts. These pieces of furniture eventually turned into what are now known as "dressing tables" or vanities.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment

All comments will be subject to approval by a moderator. Comments may fail to be approved if the moderator deems that they:

--contain unsolicited advertisements ("spam")

--are unrelated to the subject matter of the post or of subsequent approved comments

--contain personal attacks or abusive/gratuitously offensive language